The Challenge

Trade policy work is complex and ever-evolving. From opening new markets, addressing phytosanitary barriers to trade and navigating bi-and multi-lateral trade agreements, Bryant Christie Inc. has experienced it all over the span of our 30-plus-year history. Below is a brief retelling of some behind-the-scenes stories of this work done to assist our clients and the mission that guides us as we navigate the world of trade today.

"How Does One Measure a Fish?"

How does one measure a fish—from the nose to the top, middle, or bottom of the tail? In 1993, Bryant Christie Inc. (BCI) was hired by a California cherry exporter to resolve an expensive problem. The exporter had produced 75,000 cherry cartons for export to Japan at significant cost, only to have them rejected by Japanese trade officials.

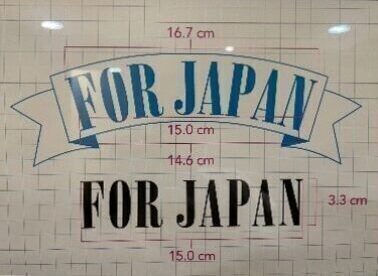

A strict interpretation of Japanese regulations required the “For Japan” lettering on each box to be no less than 3.3 cm in height and 15 cm in length. However, a design element caused the otherwise correct lettering to curve, making its length 16.7 cm at the top, 15 cm in the middle, but only 14.6 cm at the bottom.

Resolving the issue took months and many hours of effort by BCI and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Ultimately, rather than simply agreeing with our measurement rationale, the Japanese amended the regulation and reduced the minimum length requirement to 14.5 cm. This experience provided an early lesson in policy negotiation and cultural nuances.

This case exemplifies BCI’s early work in market access and trade policy. While some aspects of our work remain the same—resolving technical issues that restrict food and agricultural exports—the trade environment and the scope of our efforts have evolved dramatically.

Opening Global Markets: The Early Years

Much of BCI’s early trade policy work centered on opening new global markets for specialty crops by addressing phytosanitary (plant health) barriers to trade. As tariffs decreased through multilateral trade agreements (e.g., GATT and later the WTO), countries began protecting their agricultural industries by erecting barriers based on plant health concerns.

BCI collaborated with the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to develop scientifically justifiable measures to mitigate these concerns. When political challenges arose, we worked with the USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) and the U.S. Trade Representative’s office to pressure foreign governments into complying with international obligations. Although these efforts often spanned years or even decades, they were largely successful, delivering billions of potential new consumers and significant international sales to American growers.

The 1994 Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Agreement, negotiated during the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), provided a vital foundation. The agreement required members to base their trade systems on scientific principles. However, hopes for further global trade facilitation faded with the failed 1999 WTO Ministerial Conference in Seattle, which was marked by protests and disruptions.

Free Trade Agreements and a Changing Trade Landscape

Despite challenges at the WTO, the early 2000s saw a surge in bilateral and multilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). BCI contributed to many, including U.S. agreements with Chile, Singapore, Australia, Morocco, South Korea, and the CAFTA-DR region. These FTAs reduced tariffs and established special committees to address SPS barriers, resolving long-standing quarantine issues and opening new markets.

This period was marked by optimism about globalization’s potential to reduce geopolitical conflict and improve economic conditions. However, the subsequent decade saw a rise in protectionism, fundamentally altering the trade landscape.

Focus on Pesticide Residue Standards

By the mid-2000s, BCI’s market access work increasingly focused on pesticide maximum residue levels (MRLs). Advances in testing and enforcement enabled countries to set unique national standards rather than harmonize them globally. These varying standards created significant market access challenges, often resulting in costly shipment rejections.

To address this, BCI worked with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and USDA to develop and manage the BCGlobal MRL Database, now owned by FoodChain ID. This comprehensive database allows exporters to compare pesticide standards across over 155 countries, mitigating risks and facilitating compliance.

In 2021, a critical MRL issue arose when Korea eliminated a temporary MRL for a pesticide widely used on U.S. potatoes. The resulting threat to $100 million in U.S. fry exports was resolved within five months through coordinated efforts by BCI, the U.S. and Korean governments, the U.S. potato industry, and the registrant.

Emerging Challenges and Continued Commitment

Today, BCI addresses a range of market access challenges, including tariff issues, plant health, and MRL policies. New concerns, such as packaging and labeling standards and sustainability requirements, continue to emerge.

Today, the world of international trade is fluid. Yet, our mission since BCI’s founding in 1992 remains the same: helping U.S. food, agriculture, and beverage exporters open, access, and develop international markets. While the issues may change, our goal and approach remain constant. It is incredibly satisfying work that we are passionate about.