The exclusion of the United States in multilateral trade agreements has had a negative impact on the ability of exporters to compete in the global marketplace.

By Adam Hollowell

Originally posted December 12, 2022, updated October 26, 2023

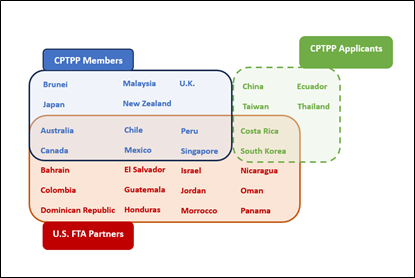

Earlier this year, Brunei became the latest and the last of the original signatories to ratify the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, or CPTPP. The agreement, which emerged out of the ashes of U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, now has a membership of twelve countries after the accession of the United Kingdom in July 2023, stretching the notion of a "Trans-Pacific" agreement. To date, the U.K. is the only new member to join the agreement; however, there is a healthy waiting list of markets seeking to accede including Taiwan, China, Ecuador, and Costa Rica. Other countries, including the Philippines, South Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia are also readying applications.

This expanding membership stands to benefit from the CPTPP’s comprehensive tariff reductions, which include the elimination of tariffs on over 90 percent of goods, including agricultural products.

The maturity of the CPTPP agreement and its expanding membership has two notable consequences for U.S. agricultural exports.

The first is to increase the tariff headwinds facing U.S. exporters. The U.S. is losing sales and market share because of tariff differences.

Take U.S. frozen fry exports to Vietnam. Valued at almost $23 million in 2019, this figure now stands at $12.3 million. One major reason is the 12 percent import tariff faced by U.S. exporters. The same product from competitors in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada enters Vietnam tariff-free because of the CPTPP.

This same situation is playing out for a wide range of U.S. agricultural exports to Vietnam. Apples, citrus, blueberries, cherries, as well as many processed agricultural goods, all face higher import tariffs in Vietnam compared to competitor products from CPTPP member countries. To add insult to injury, the U.S. was the key player in negotiating these tariff concessions in the original TPP agreement and which now benefit U.S. competitors.

Challenges also remain in traditionally strong U.S. export markets such as Japan. The U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement negotiated under the Trump Administration included critical tariff concessions for many U.S. agricultural products, but not all. Japanese tariffs on frozen blueberries and fresh grapes remain in place with no prospect for further reduction. Meanwhile, competitors in the CPTPP such as Canada and Chile enter duty-free.

Malaysia’s ratification of CPTPP in September 2022 pose a similar challenge to U.S. suppliers, as it marks the country’s first trade agreement with Canada, Mexico, and Peru. All three countries will gain tariff-free access to Malaysia for their agricultural exports. In contrast, the U.S., without a free trade agreement with Malaysia, will stay at higher tariff rates. This will mean U.S. exporters to Malaysia of fresh grapes, citrus, and many other specialty crops, will continue to face an additional five percent import tariff that competitors in Canada, Mexico, or Peru do not.

These tariff differences seem small, but viewed in the broader context of U.S. price competitiveness in Asia, they are significant and have real-world impacts. They risk the loss of contracts, and the movement of production and supply chains away from the U.S. When sustained, they threaten jobs and opportunities in agricultural communities throughout rural America.

The second notable consequence of CPTPP expansion has been to increase pressure on the Biden Administration to rethink its U.S. trade policy agenda, which so far has not prioritized the pursuit of tariff reduction. The Administration’s flagship trade initiative, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), includes a trade pillar but does not include any ‘traditional’ market access or tariff reduction elements.

Despite concerns from both Congress and stakeholders in U.S. agriculture, the Biden Administration has so far refused calls to adjust its approach toward tariffs. Instead, officials have presented the omission of tariffs as a deliberate feature of IPEF and have cited the pursuit of tariff reduction as part of a practice that has led to fragility in U.S. trade policy.

This perspective and the omission of tariffs has been criticized, not least because of the benefits of traditional U.S. leadership on market access and tariff liberalization.

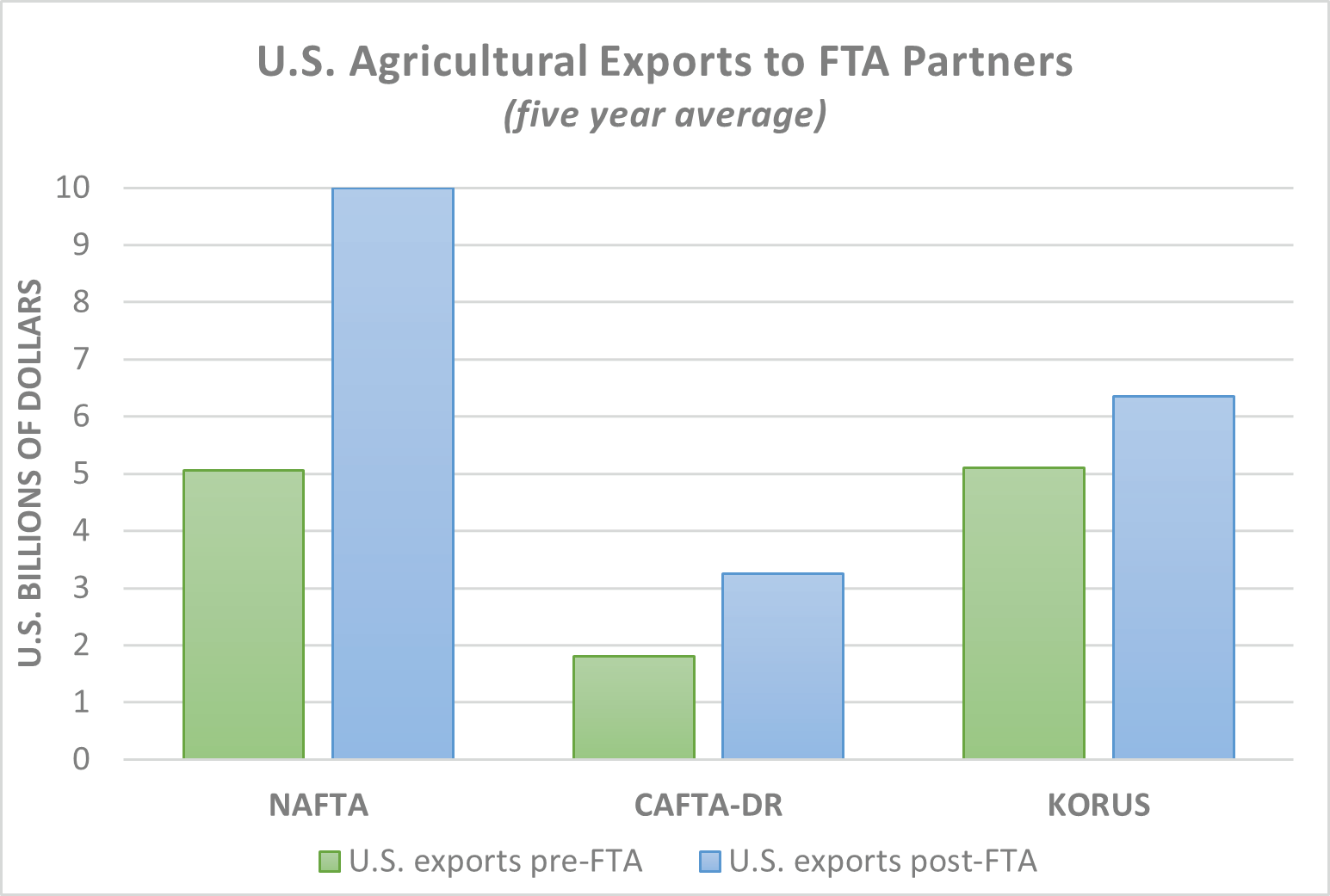

The U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement, formally NAFTA, reshaped U.S. trade relations with its neighbors and eliminated virtually all tariffs on goods, including agriculture. The result has been a vast increase in U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico, from $9 billion in 1993 to over $50 billion in 2021.

Further south, the U.S. trade agreement with countries in Central America and the Dominican Republic, informally known as CAFTA-DR, resulted in immediate duty-free access for more than half of U.S. farm exports when it took effect in the mid- 2000s, with the remaining tariffs phased out over twenty years. Exports to the six CAFTA-DR markets have grown rapidly as a result, from $1.9 billion in 2005 to over $6.7 billion in 2021; an increase of over 250 percent.

Similar inroads have been made in some Asian markets. In Korea, for example, exports of U.S. agricultural products have increased 53 percent since the implementation of the U.S.-Korea trade agreement (KORUS), which prominently included the elimination of Korean tariffs on over 95 percent of U.S. exports.

Two decades of U.S. leadership on free trade and tariff liberalization have paid dividends for U.S. agriculture and expanded global market opportunities for U.S. producers and exporters. But if you do not move forward, sooner or later you begin to move backward, and the Biden Administration’s current ambivalence towards agricultural tariff reduction risks ceding U.S. advantage to our competitors, who continue to prioritize tariffs.

In an increasingly competitive global landscape, it is more important than ever that tariffs are part of the picture and prioritized in U.S. trade policy. We live in a changing world with new pressures and concerns. But the fundamentals still matter. Tariffs matter. And the U.S. is falling behind.

For more on global export news, insights and information please visit Bryant Christie Inc.’s website, sign up for our e-newsletter and follow us on LinkedIn.